EcoTipping Points Story In-Depth

In a remote fishing village in the Philippine archipelago, coastal fishers responded to falling fish stocks by working harder to catch them. The combination of dynamite, longer workdays, and more advanced gear caused stocks to fall faster. On the edge of crisis, this small community decided to create a no-take marine sanctuary on 10% of its coral-reef fishing grounds. This initiative sparked a renaissance of not only their fishery, but also their cherished way of life.

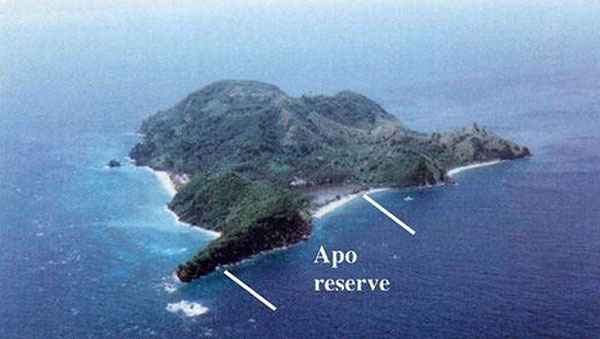

Apo Island provides a relatively simple but very real case study for exploring how EcoTipping Points work in practice. Apo is a small island (78 hectares), 9 kilometers from the coast of Negros in the Philippine archipelago. The island has 145 households and a resident population of 710 people. Almost all the men on the island are fishermen. The main fishing grounds are in the area surrounding the island to a distance of roughly 500 meters, an area with extensive coral reefs and reaching a water depth of about 60 meters.

Fishermen use small, paddle-driven outrigger canoes, though a few fishermen (particularly younger ones) have outboard motors on their canoes. The main fishing methods are hook and line, gill nets, and bamboo fish traps.

Before then, there was a stable fishery with ample harvest to support fishermen and their families. During the years following World War II the growing human population and increasing fishing pressure made the fishery increasingly vulnerable to unsustainable fishing. The “negative tip” came with the introduction of four destructive fishing methods to the Philippines:

- Dynamite fishing, which started with explosives left over from World War II and gained momentum by the 1960s;

- Muro-ami (from Japan). Fish are chased into nets by pounding on coral with rocks.

- Cyanide, introduced during the 1970s for the aquarium fish trade. Aquarium fish are no longer collected in this region, but cyanide remained.

- Small-mesh nets. Worldwide marketing of newly developed nylon nets brought small-mesh beach seines and other small-mesh nets to the region in the 1970s.

Destructive Fishing Methods Increase Yields, Introduce Problems

Dynamite, cyanide, muro-ami, and small-mesh nets are more effective than traditional Filipino fishing methods, but they are seriously detrimental to the sustainability of the fishery. Not only do they make overfishing and immature fish harvesting easier, they also damage fishing habitat. These fishing methods have been illegal since regulations were imposed in the early 1980s. The Philippine Coast Guard and National Police are responsible for enforcing fishing regulations, but their vast areas of jurisdiction have made it virtually impossible for these agencies to stop destructive fishing.

The introduction of destructive fishing methods set in motion a vicious cycle of declining fish stocks and greater use of destructive methods to compensate for deteriorating fishing conditions. Damage to the coral reef habitat is now extensive throughout much of the Philippines, and fish stocks are generally low.

Fish stocks in the most degraded areas are down to 5-10% of what they were 50 years ago. Though catches in degraded areas are not sufficient to support a fisherman full-time, the fishery continues to be depressed by a large number of fishermen, many of them part-time and many using illegal fishing methods that they consider the only practical way to catch fish under these conditions. The problem is exacerbated by illegal encroachment of larger commercial fishing boats with gear such as purse seines and ring nets wherever enforcement is lax and nearshore fishing conditions are good enough to make encroachment worthwhile.

Step 1: Inspiration

The prelude to the positive tip for Apo Island began in 1974 when Dr. Angel Alcala (director of the marine laboratory at Silliman University in Dumaguete City) and Oslob municipality (Cebu) initiated a small marine sanctuary, the region's first, at uninhabited Sumilon Island (about 50 km from Apo). Dr. Alcala and some of his colleagues at Silliman University visited Apo Island In 1979 to explain how a marine sanctuary could help to reverse the decline in their fishery, a decline that had become obvious to everyone. By that time, fish stocks on the Apo Island fishing grounds had declined so much that fishermen were compelled to spend much of their time traveling as far as 10 km from the island to seek more favorable fishing conditions.

Dr. Alcala took some of the fishermen to see the marine sanctuary at Sumilon Island, which by then was teeming with fish. They were able to see how the sanctuary could serve as a nursery to stock the surrounding area, but they were not completely convinced. Marine sanctuaries were not part of Philippine fisheries tradition. After three years of dialogue between Silliman University staff and Apo Island fishermen, 14 families decided to establish a no-fishing marine sanctuary on the island. A minority of families was able to do it because the barangay captain (local government leader) supported the idea.

Step 2: Establishing A Marine Sancuary

The positive tip for Apo Island came with actual establishment of a marine sanctuary in 1982. The fishermen selected an area along 450 meters of shoreline and extending 500 meters from shore as the sanctuary site - slightly less than 10% of the fishing grounds around the island. The sanctuary area had high quality coral but few fish. It required only one person watching from the beach to ensure that no one fished inside the sanctuary, guard duty rotating among the participating families. Fish numbers and sizes started to increase in the sanctuary, and "spillover" of fish from the sanctuary to the surrounding marine ecosystem led to higher fish catches around the periphery, eventually to a distance of several hundred meters. In 1985 all island families decided to support the sanctuary and make it legally binding through the local municipal government.

Step 3: Growth and Replication

When the fishermen saw what happened in and around the sanctuary, they concluded that fishing restrictions over the island's entire fishing grounds should be able to increase fish numbers there as well. With technical support from a coastal resource management organization, the fishermen set up a Marine Management Committee and formulated regulations against destructive fishing and encroachment of fishermen from other areas on their fishing grounds. They established a local "marine guard" (bantay dagat) consisting of village volunteers to police the fishing grounds. It was no longer necessary to guard the sanctuary per se because everyone accepted its status as a no-fishing zone. The main task of the marine guards today is to check boats that enter their fishing grounds from other areas. They do not seem to worry about Apo Island fishermen because sustainable fishing has become an integral part of the island culture.

Although available data do not allow a precise comparison of current fish stocks and catches on the Apo Island fishing grounds with fish stocks and catches when the sanctuary was established, the data indicate that catch-per-unit-effort more than tripled by the mid-1990s and has not changed much since then (Russ et al. 2004). The larger and commercially more valuable fish (e.g., surgeon fish and jacks) increased more slowly and are in fact still increasing. This scenario is confirmed by the fishermen's subjective impression of what has happened.

Better quality of life

Interestingly, the total catch by island fishermen is about the same as 23 years ago when the sanctuary began. This is because the fishermen have responded to the increase in fish stocks by reducing their effort instead of catching more fish. Fishermen no longer must travel long distances to fish elsewhere. Fishing is good enough right around the island. A few hours of work each day provides food for the family and enough cash income for necessities. The fishermen worked long hours before. Now they enjoy more leisure time. If they wish, they can use some of the extra time for other income generating activities such as transporting materials or people between the island and the mainland. The most prominent reason for earning extra money is to fund higher education for their children.

Biodiversity brings coral-reef tourism

The striking abundance and diversity of fish and other marine animals (e.g., turtles and sea snakes) around the island have attracted coral reef tourism (Cadiz and Calumpong 2000). The island has two small hotels and a dive shop, which employ several dozen island residents. In addition, diving tour boats come daily from the nearby mainland. A few island households take tourists as boarders, and some of the women have tourist related jobs such as catering for the hotels or hawking Apo Island T-shirts. The island government collects a snorkeling/diving fee, which has been used to finance a diesel generator that supplies electricity to every house in the island's main village during the evening. The tourist fees have also financed substantial improvements for the island's elementary school, garbage collection for disposal at a landfill on the mainland, and improvements in water supply.

More Apo Island children attend high school and college

Tourist revenue has also provided family income and "scholarships" (from one of the island hotel owners) to finance more than half the island's children to attend high school on the adjacent mainland, and many continue to university. Almost all university graduates and many high school graduates stay on the mainland with a job that allows them to send money to their family back on the island. A few return for professional work on the island such as elementary school teacher, and some aspire to return to contribute to the island's health services, governance, or marine ecosystem management. Remittances from family members living off-island are used mainly for private infrastructure such as house improvements. Many people who live away from the island live close enough for frequent visits to their family on the island.

A Model For Local Fishing Communities

Apo Island has served as a model for fishing communities on the adjacent mainlands of Negros and Cebu. The head of Apo Island's local government visits other fishing villages to explain the sanctuary, and people from other villages visit Apo to see what it's all about. In 1994 the Apo Island example, and the fact that Dr. Alcala was Minister of Natural Resources, stimulated the Philippine government to establish a national marine sanctuary program that now has about 700 sanctuaries nationwide. Not all are functioning as well as they should, but many seem to be on the same path as Apo (see Replication of Apo Island’s Example to Other Villages in the Philippines). While the national network has provided benefits, it has also reduced the autonomy of Apo’s local government and increased national government interference in management of the sanctuary and the use of revenues from tourist fees.

"The Sanctuary Saved Our Island"

The Apo Island story is not a fairy tale. I visited Apo Island, I talked to island residents, and everyone told me the same story. They firmly believe that the sanctuary saved their island. The story is documented by scientific publications that include 25 years of monitoring the island fishery and ecological conditions in the sanctuary. The following publications provide an overview: Russ and Alcala (1996), Russ and Alcala (1998), Russ and Alcala (1999), Alcala (2001, p. 73-84), Maypa et al. (2002), Raymundo and Maypa (2003), Russ and Alcala (2004), Russ et al. (2004), Alcala et al. (2005), Raymundo and White (2005).

Meeting New And Continuing Challenges

Apo Island is not perfect. There are personal conflicts, political factions, complaints about government, and many other things typical of human society around the world. People on the island are not particularly affluent. Houses do not have piped water; residents must collect water from faucets strategically placed around the village. Medical services on the island are limited, though doctors can be reached with a half-hour boat ride to the mainland. Many feel that the economic benefits of tourism, which go mainly to the hotel owners, should be distributed more evenly. While participation in the national sanctuary program has reinforced the status of the Apo Island sanctuary and provided networking benefits, it also means island fishermen no longer have complete control of sanctuary management or funds that come from diving and snorkeling fees.

As tourism has increased, concern has grown about the impact of snorkeling and diving on the sanctuary and the fishery (Reboton and Calumpong 2003). The island government has instituted restrictions on the number of tourists in the sanctuary to limit damage to coral there. Fishermen have complained that divers scare fish away from where they are fishing and sometimes damage their fish traps or release fish from the traps. As a consequence, divers are not allowed to swim within 50 meters of fishing activities and the prime fishing area is completely off limits to divers. Some island inhabitants are not satisfied with enforcement of these restrictions, and dialogue continues about what should be done to protect the marine ecosystem from damage by tourism.

Improved Quality of Life

But overall, there is a conspicuous atmosphere of well being and satisfaction with quality of life on the island. This is not because the island inhabitants are ignorant or inertial. They value their quality of life and the quality of the island's marine ecosystem, and they want to keep it that way. Their experience with the sanctuary has taught them an important lesson. It is necessary to change some things by community action in order to keep other very important things the same. They are committed to keeping their island's fishing grounds sustainable.

Twenty years ago the island inhabitants changed the way they managed their fishing activities. Now they need to make some changes in the size of their families. Everyone agrees that the island's increasing human population is a serious threat to its future. A family planning program was initiated two years ago, and contraceptives are readily available at a small community-operated family planning center. Most families are using them. Young people, even elementary school children, readily express their intention to have a small family. Immigration of people who are not descended from Apo Island families is not allowed.

Commitment To Protecting Their Newly Sustainable Resource

The sanctuary has changed the way that people on the island view their world. The fishermen say that before the sanctuary their strategy was to fish a place with destructive methods until it was no longer worth fishing and then move to a new place that was not yet degraded. Now they are committed to keeping one place, their island's fishing grounds, sustainable. Before, they expected government agencies responsible for enforcing fishing regulations to do so and complained when it didn't happen. Now they enforce their own regulations themselves. This spirit of local initiative has extended to developing the island's infrastructure and assuring that island children get the education they need for a decent future. Organization for fisheries management has stimulated the community to organize in other ways as well – particularly women's groups. The island has a locally operated women's credit union and a women's association for selling souvenirs to tourists.

Apo Island’s marine sanctuary is sacred to the people there. They say it saved their coral-reef ecosystem, their fishery, and their cherished way of life. The sanctuary was an EcoTipping Point – a “lever” that reversed decline and set in motion a course of restoration and sustainability.

Authors & Contributors

Author: Gerry Marten

Site visit assistance and editorial contributions: Ann Marten

This story is excerpted from Environmental Tipping Points: A New Paradigm for Restoring Ecological Security, Journal of Policy Studies (Japan), No.20 (July 2005), pages 75-87

Acknowledgements

Angel Alcala, Alan White, Laurie Raymundo, Aileen Maypa, and Mario Pascobello provided information for the Apo Island story. Portia Nillos helped in numerous ways during my visit to Apo Island.

References

- Alcala, A. C. 2001. Marine reserves in the Philippines: historical development, effects and influence on marine conservation policy. Bookmark, Makati City, Philippines.

- Cadiz, P. L., and H. P. Calumpong. 2000. Analysis of revenues from ecotourism in Apo Island, Negros Oriental, Philippines. Proceedings of 9th International Coral Reef Symposium (Bali, Indonesia, 23-27 October 2000), Volume 2:771-774.

- Liberty’s Community Based Lodge and Paul’s Community Diving School, Apo Island.

- Maypa, A.P., G. R. Russ, A. C. Alcala, and H. P. Calumpong. 2002. Long-term trends in yield and catch rates of the coral reef fishery at Apo Island, central Philippines. Marine Freshwater Research 53:207-213.

- Raymundo, L. J., and A. P. Maypa. 2003. Chapter 14. Apo Island marine sanctuary, Dauin, Negros Oriental. Pages 61-65 in Philippine coral reefs through time. The Marine Science Institute, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Philippines.

- Raymundo, L. J., and A. T. White. 2005. 50 years of scientific contributions of the Apo Island experience: a review. Silliman Journal (50th Anniversary Issue), Silliman University, Dumaguete, Philippines.

- Reboton, C., and H. P. Calumpong. 2003. Coral damage caused by divers/snorkelers in Apo Island marine sanctuary, Dauin, Negros Oriental, Philippines. Philippine Scientist 40:177-190.

- Russ, G. R., and A. C. Alcala. 1996. Do marine reserves export adult fish biomass? Evidence from Apo Island, central Philippines. Marine Ecology Progress Series 132:1-9.

- Russ, G. R., A. C. Alcala. 1998. Natural fishing experiments in marine reserves 1983-1993: community and tropic responses. Coral Reefs 17:383-397.

- Russ, G. R., and A. C. Alcala. 1999. Management histories of Sumilon and Apo marine reserves, Philippines, and their influence on national marine resource policy. Coral Reefs 18:307-319.

- Russ, G. R., and A. C. Alcala. 2004. Marine reserves: long-term protection is required for full recovery of predatory fish populations. Oecologia 138:622-627.

- Russ, G. R., A. C. Alcala, A.P. Maypa, H. P. Calumpong, and A. T. White. 2004. Marine reserve benefits local fisheries. Ecological Applications 14:597-606.

Apo Island Ingredients For Success

Vicious cycles – the feedback loops driving decline - are central to the Apo Island story. Positive change was set in motion when vicious cycles were reversed, transforming them into virtuous cycles that drove restoration with as much force as the vicious cycles drove decline. What does it take to reverse vicious cycles and transform them into virtuous cycles? The Apo Island story shows us key ingredients for success. Read more...

Related Lesson Plan

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, ne sea vocent scripta abhorreant, facilisi explicari mel ne, ut quo vide ridens. Mei ex quodsi inciderint, quo ad quas deleniti definitionem, vis no wisi graecis offendit. Ius ut everti detraxit expetenda, meis civibus consectetuer ea usu. Ad qui option facilisis consequuntur, pro omnis aliquip vulputate te. Solum affert expetenda eos te, et vim sale iudico impetus, in appetere postulant ius. Read more....

Apo Island Feedback Analysis

The negative tipping point occurred throughout the Philippines with the introduction of destructive fishing methods such as dynamite, cyanide, and small-mesh fishing nets. Two interlocking and mutually reinforcing vicious cycles were set in motion:

- The use of destructive fishing methods reduced fish stocks directly through overfishing, and indirectly by damaging coral habitat. Read more...

Replicating success in other communities

Portia Nillos compiled a summary of what has happened with spreading the initial success at Apo Island to other villages. The report below represents the first step in a larger study by the EcoTipping Points Project to identify what it takes to successfully leverage a turnabout from environmental and social decline to restoration and sustainability. Read more...